The removal of a state tax incentive for investment in startups is likely to make capital scarcer for California companies most poised for high growth—harming job creation and an already vulnerable state economy in the process. The change breaks with current federal policy and puts California’s entrepreneurs at a relative disadvantage to those in other states. We estimate that investments in California’s startups will decline by a conservative 2 percent each year from the tax change—translating to a drop of at least $85-$127 million annually based on 2011 data.

In December, the California Franchise Tax Board (FTB) announced changes to capital gains tax exclusions on Qualified Small Business (QSB) stock holdings. The change stemmed from an appellate court ruling that found minimum in-state asset and employment requirements during the holding period of the QSB stock unlawful under the U.S. Commerce Clause. Rather than remove the in-state asset and employment threshold requirements, the FTB instead chose throw the baby out with the bathwater and eliminate the capital gains tax exclusions altogether—effectively increasing state taxes on investments held in QSBs from 4.65 percent (under a 50 percent exclusion) to 9.3 percent (under zero exclusion).

The real attention grabber has been the FTB’s choice to make the change retroactive to 2008—with penalties and interest—despite the fact that investors were following what was then current law. While investors are up in arms over this, entrepreneurs may actually have the most to lose moving forward.

Capital is the lifeblood of startups. This move by the FTB, which amounts to a tax hike for investors, will likely make capital scarcer for young businesses. Fewer startups means less job growth; for the last 30 years, young companies have provided all of the net new job creation in California and the United States as a whole.

Matching an existing framework with data on California, it’s possible to generate a conservative, back-of-the envelope, estimate of investment startups in the state might lose. This drop would likely have a negative impact on the California economy—not only have startups been the engine of new job creation in the state, but the QSB capital gains tax exclusions were targeted especially at businesses with the highest growth potential.

Estimating Investment Impact of Tax Change

A 2012 Kauffman Foundation report provides the framework for estimating the impact of tax changes on early-stage investments in startups. The report yields a conservative estimate of the additional investment in startups that would occur if 100 percent of the capital gains held at least five years were excludable from federal taxation, compared with an earlier exclusion of 50 percent. In other words, the report tells us how much investments of this nature might increase when taxes are reduced.

We employ that same framework here but move in the opposite direction, answering the question: how much would investments in startups decline from what amounts to a tax increase? Then we apply this estimate to data on investments in California startups.

Let’s unpack the potential investment response to the tax increase by using a hypothetical example. The Kauffman report states that a reasonable assumption for a real pre-tax return on privately held investments in startups in the current interest rate environment is 10 percent. At least one prominent angel investor group agrees, and so do we.

Under this assumption, an investment of $100 would be worth $161 after five years on a pre-tax basis. If the tax rate were 4.65 percent, as it was under the previous 50 percent exclusion in California, that same investment would be worth $158, for an average annual return of 9.6 percent. Under a 9.3 percent tax rate regime (zero exclusion), that same investment would be worth $155—returning 9.2 percent per year on average. Capital gains in QSBs are currently fully excludable from federal income taxes and were in 2011 as well—the base year used in our analysis.

A change in the effective tax from 4.65 to 9.3 percent results in a 4 percent drop in the average annual return on the investment (from 9.6 percent to 9.2 percent). Based on previous research on the topic, and conversations with experts in the field, the Kauffman report concluded that the responsiveness (the “elasticity”) of such a change in the rate of return on aggregate investments is a conservative 0.5—or half the change in return. In other words, the 4 percent decline in a typical return would result in a 2 percent drop in investment overall. Two percent may not seem like a big decrease, but when applied to a large base like in California, it can be.

To see how big of a dent 2 percent could make, the baseline estimate of equity invested in California startups is tabulated from three sources of “seed funding”:

Seed-Stage Investments in California Startups (2011)

| Source of funding | $ (in Billions) |

| Venture capital | $0.5 |

| Angel investors | $2.8-$4.4 |

| Entrepreneurs' equity | $0.8-$1.2 |

| Total | $4.1-$6.1 |

Sources: PricewaterhouseCoopers MoneyTree, Center for Venture Research, Silicon Valley Bank, Kauffman Foundation; Engine calculations

In total, an estimated $4.1-6.1 billion was invested in California seed-stage startups in 2011. It is reasonable to assume that essentially all of these seed funds were invested in traditional C corporations—the type of company that is most suitable for startups and is eligible for the QSB tax deduction. For scope, that amounts to between 32 and 47 percent of such investments in the entire United States.

With a baseline of $4.1-6.1 billion, and a 2 percent reduction in investments from the tax change, we’re left with a decline of $85-127 million in investment in startups each year in California. Now, $85-127 million per year may not sound like a whole lot of money relative to total investments in startups broadly, but over ten years it totals between $853 million and $1.27 billion. Moreover, whether we are talking about an annual or decade-long framework, considering that seed-stage companies may receive as little as $15,000 in funding (though a typical amount is in the hundreds of thousands), we’re talking about a lot of companies that may be adversely affected.

What’s more, this is almost certainly an underestimate of the value of investments in California startups and the effect the tax change would have. To begin, the Kauffman report reiterates that its framework is likely to yield conservative estimates. Most notably, it states that the elasticity estimate of 0.5 is likely conservative—meaning that for each 1 percent decline in a typical rate of return, overall investments would fall by more than 0.5 percent.

Secondly, since QSB status in California applies to companies with up to $50 million in assets, many businesses beyond the “seed/startup stage” would qualify. As a result, we are surely undercounting the pool of investment in the state that would be affected by the tax change.

Third, the 2011 statutory state tax rate applied here (9.3 percent) is lower than the marginal rate charged to those with incomes above $1M (10.3 percent), which would apply to a non-trivial number of investors in startups. These investors would be adversely affected even more than our rough estimates indicate.

Finally, the Kauffman framework was previously applied to federal tax—which would be applied uniformly across states. Holding federal tax rates and all other factors constant, other states would have an advantage against California. According to the Angel Capital Association, twenty states have tax incentives for angel investors and California isn’t one of them. For example, states like Wisconsin are actively partnering with investors to increase investments in startups.

In addition to all of this, Proposition 30, which was adopted by California voters in November, raises state income taxes to varying degrees on individuals who earn more than $250,000 per year. Though this is outside the scope of our analysis—both because the year studied pre-dates that particular tax hike and because arguing the merits of state tax policy broadly goes beyond what we’d like to accomplish here—it will further compound the issue, potentially leading to even more declines in investments in California startups.

Economic Impact

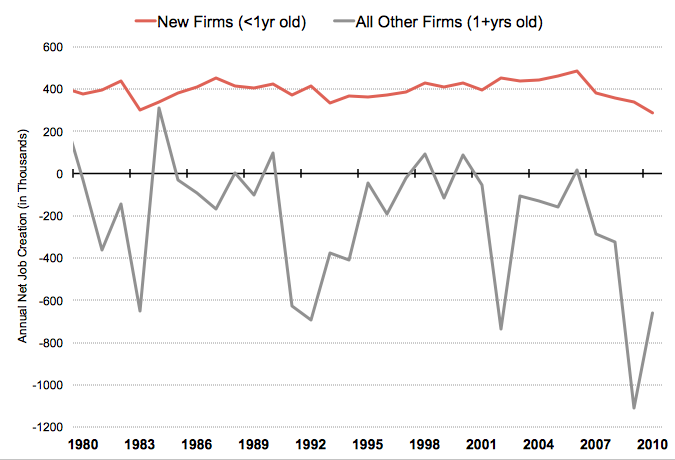

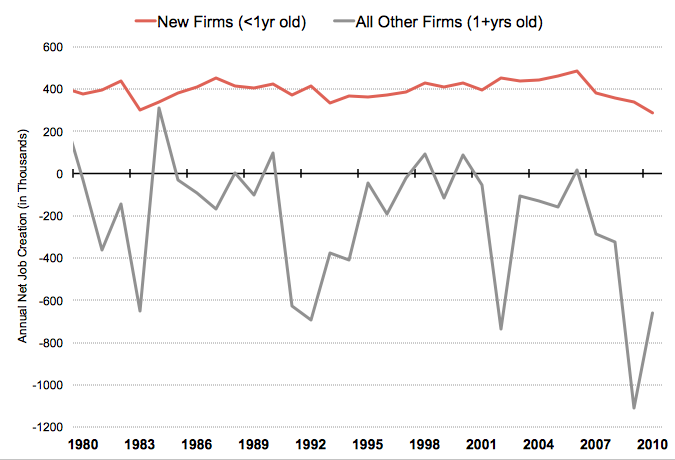

Though data are not readily available to directly tie investments in QSB-type businesses specifically to the economic impact in California, data from the Census Bureau can illustrate the important role that new businesses play in job creation in the state.

California Private-Sector Annual Net Job Creation by Firm Age (1980-2010)

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Business Dynamics Statistics

Between 1980 and 2010, businesses in their first year added an average of 398,193 new jobs each year. Companies aged one year or more, as a group, subtracted an average of 192,501 each year during that same period. This occurred because the forces of job destruction (through business contractions and closures) were stronger than the forces of job creation (through firm births and expansions) for businesses older than a year old as a group. In other words, outside of startups, net job creation in California was negative during the past three decades.

In addition to the job creation dynamics of new firms, among existing businesses it is young firms (those less than five years old) that have the biggest effect on job creation. Taken together with the chart above, we can say that new and young firms are responsible for all net new job creation during the past few decades.

Conclusion

The FTB’s tax change is likely to reduce investments in California’s startups by a conservative 2 percent each year, translating to $85-$127 million fewer investments annually based on 2011 data. This can’t be a good thing for the economy or job creation in the state. At a time when the state unemployment rate hovers around 10 percent, California can hardly afford to place any of its companies at a competitive disadvantage—especially not those poised for high growth. On top of that, a recent survey of small businesses sponsored by the Kauffman Foundation found California to be among the least friendly for entrepreneurs.

Though it is understandable that state authorities are searching for ways to improve the fiscal situation of California, this isn’t a good way to go about it. The entire point of providing a tax incentive for these investments is to make them more attractive to investors, relative to others, precisely because seed-stage investments are very risky and because startups have important spillovers to the economy—namely that they fuel economic growth and job creation.

Moving forward, not only should state policymakers reinstate the QSB capital gains exclusion, they should extend it—making capital gains on these investments fully excludable. There is already precedent for this at the federal level too: in 2010 Congress temporarily made these investments fully excludable and recently extended this policy through 2013. If Washington can see the wisdom in doing this, why can’t Sacramento?

Ian Hathaway is the research director at Engine

A few weeks back, we posted the

A few weeks back, we posted the